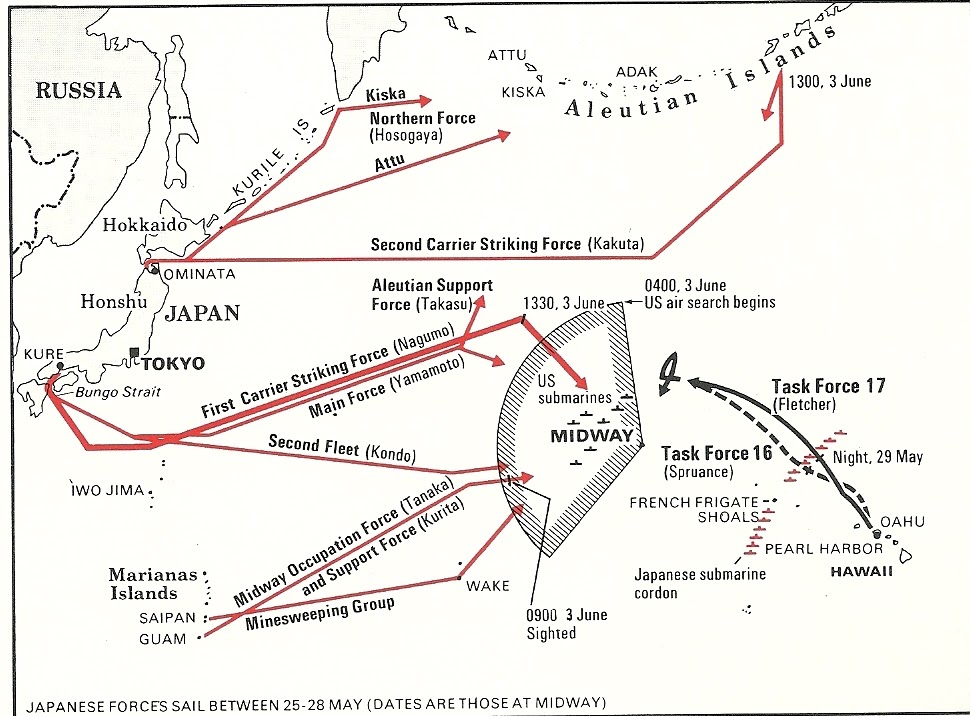

In May the US knew that another major operation was being planned by the Japanese Fleet, to be carried out by the end of that month or early in June. The precise objective of this operation was not known at first, but by the middle of May the U.S. had not only learned that the Japanese target was Midway But also had ascertained with considerable accuracy the makeup of forces to be deployed. By early June, Midway plane strength had been augmented by the arrival of 16 Marine Corps dive bombers, 7 Wildcat fighters, some 30 Navy patrol flying boats, and 18 B-17s and 4 B-26s bombers from the Army. More than 2,000 garrison troops were deployed ashore, and many antiaircraft batteries were installed. A number of motor torpedo boats (PT-Boats) were also brought in to be employed for short-range patrol and night attack missions. In addition, three submarine patrol arcs were set up at distances of 100, 150, and 200 miles from Midway, with a total of 20 submarines on station by 4 June.

The Unites States Pacific Fleet was determined to oppose the invasion of Midway with all the strength that it could muster. On that point the calculations of the Combined Fleet had been correct. Midway was so important to the safety of Hawaii that American Fleet could not let it be taken without a battle.

What about the submarine cordons? Far to the South, The submarine elements assigned to the cordon lines between Midway and the main Hawaiian Islands at last took up their stations during 3 June, two days behind schedule. Each submarine remained submerged during the day and surfaced at night, never relaxing its lookout for enemy forces coming from the direction of Pearl Harbor. But they had arrived too late. The enemy (US) ships had already passed positions of the cordons and moved far to the west.

The enemy carrier groups were to the north of Midway, well beyond the cordon lines, waiting to strike at the flank of the unsuspecting enemy forces. The trouble of course, lay in the fact that the entire Japanese invasion plan, including the provisions for the flying boat reconnaissance of Pearl Harbor and the submarine cordons, was based on the assumption that tactical surprise could be achieved and the enemy fleet reaction would not get underway until after the assault on Midway had begun.

The Attack:

At about 0300 hrs 4 June the crew of Akagi was preparing to launch its planes for the attack on Midway. Search Planes were launched at 0430, simultaneously with the departure of the first Midway attack wave. But, the planes, which covered the center lines of the search pattern were delayed. The search planes did not get off until just before sunrise, nearly a half an hour behind schedule. But the delay in launching Tome’s plane sowed a seed that bore fatal fruit for the Japanese in the ensuing action. The fundamental cause of this failure, again lay in the Japanese Navy’s overemphasis on attack, which resulted in inadequate emphasis on search and reconnaissance.

In the predawn darkness of 4 June, at a point 240 miles Northwest of Midway, the first attack wave was took off from Admiral Nagumo’s carriers for the strike on Midway. Some 4,000 meters to port, Hiryu was also launching planes. In 15 minutes the four carriers launched 108 planes. At 0500 hours the second wave was launched. It also consisted of 108 planes. A total of 216 fighters and bombers were launched against Midway, only six failed to return. The damage to Midway was varied. All of the hangers were destroyed, runways were cratered and major damage was done to the refueling equipment, which forced the ground crews to hand fill the aircraft.

About an hour before the last of the Japanese strike planes got back to the carriers there had been a development,however, which completely altered the battle situation. The No. 4 search plane, which had been launched a full half- hour behind schedule, finally reached its 300 mile search limit, then veered North on a 60 mile dog leg before heading back. Eight minutes later the observer suddenly discerned, far off to the port, a formation of 10 ships heading southeast. Without waiting to get a closer look, the plane immediately dispatched a message to Nagumo Force “Ten Ships apparently enemy sighted. Bearing 010 degrees, distance, 240 miles from Midway. Course 150 degrees, speed more than 20 knots. Time: 0728.

Until this moment no one had anticipated that an enemy surface force could possibly appear so soon, much less suspected that enemy ships were already in the vicinity waiting to ambush us. Now the entire picture had changed. Since 0715 Akagi and Kaga, whose torpedo bombers had been held back in the second attack wave, had been hurriedly rearming them with 800 kilogram bombs in place of torpedoes for another strike at Midway. The rearming by this time had been more than half completed. Admiral Nagumo had ordered the rearming of two carriers torpedo bombers to be immediately suspended and directed his whole Force to prepare for a possible attack on enemy ships. Finally at 0809, the reply came in: Enemy ships are five cruisers and five destroyers. The relief inspired by the 0809 message, however, was short lived. At 0820 the Tone plane was heard from again, and this time it reported, “Enemy force accompanied by what appears to be aircraft carrier bringing up the rear." This information electrified everyone, but there was a residue of doubt because of the words.

At 0830 still another message came in from the Tone plane. It reported: “Two additional ships apparently cruisers, sighted. Bearing 008 degrees, distance 250 miles from Midway. Course 150 degrees, speed 20 knots.

From the size of the enemy force, Admiral Nagumo concluded that it must contain at least one carrier. It was therefore essential, he decided, to attack these ships before launching another strike on Midway. However, obstacles stood in the way of a serious attack. Not only a greater part of Akagi’s and Kaga’s torpedo bombers had been rearmed with bombs by the time Admiral Nagumo ordered the rearming suspended at , but, in addition, all Zeros of the second wave fighter escort had been sent aloft to reinforce combat air patrols against the repeated attacks by enemy shore-based planes. As a result, the only planes that were armed appropriately for an attack on enemy ships and lined up the flight deck ready for take-off were the 36 dive bombers of Soryu and Hiryu

As Admiral Nagumo pondered his course of action, the return of planes from the Midway strike made a quick decision imperative. Some of the planes were in distress and the fighter escorts were running low on fuel, so their recovery could not be long delayed without risking added losses. Either the carriers decks must be cleared by launching the dive and torpedo bombers to attack the enemy without fighter cover, or the planes must be moved to make way for the recovery, thus making it impossible to launch an attack until sometime later. While the returning planes came down one after another on the flight deck, the work of rearming the torpedo bombers on the hanger deck below proceeded furiously. The crew shirts hastily unloaded the heavy bombs, just piling them beside the hanger because there was no one to lower them to the magazine. There would be cause to recall and regret this haphazard disposal of the lethal missiles when enemy bombs found their mark on the Akagi.

ENEMY (AMERICANS) CARRIER PLANES ATTACK:

As the Nagumo Force proceeded northward, our four carriers feverishly prepared to attack the enemy ships. The attack force was to include 36 dive bombers ( 18 “Val”s each from Hiryu and Soryu) and 54 torpedo bombers (18 “Kates” each form Akagi, and Kaga, and nine each from Hiryu and Soryu). It proved impossible, however, to provide an adequate fighter escort because enemy air attacks began shortly, and again most of our Zeros had to be used to defend the Striking Force itself. As a result, only 12 Zeros (three from each carrier) could be assigned to protect the bomber groups. The 102-plane attack force was to be ready for take-off at 1030.

Admiral Spruance, commanding the American force, planned to strike his first blow as our carriers were recovering and refueling their planes returning from Midway. His wait for the golden opportunity was rewarded at last. The quarry was at hand, and the patient hunter held every advantage

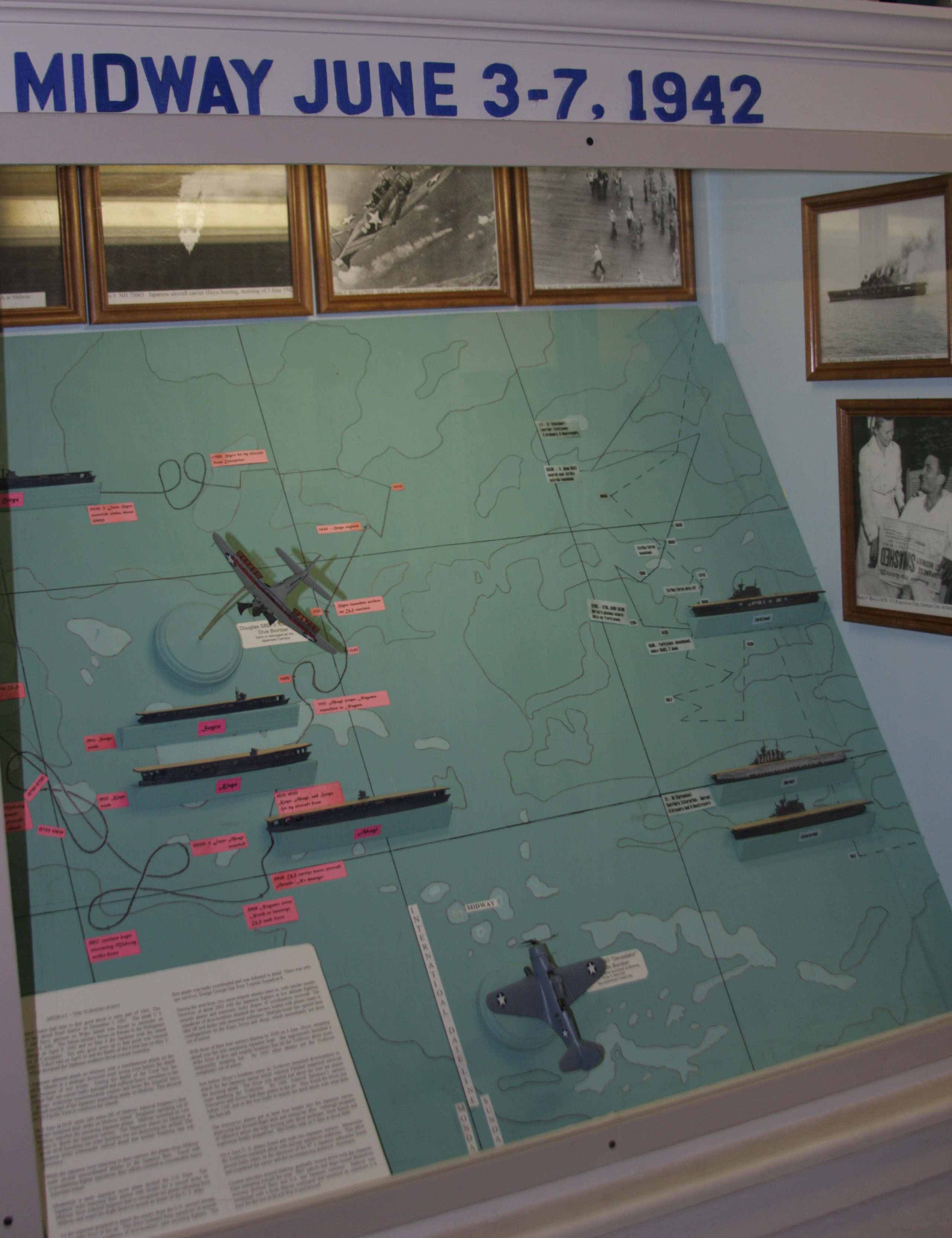

Between 0702 and 0902 the enemy launched 131 dive bombers and torpedo planes. At about 0920 our screening ships began reported enemy carrier planes approaching. Reports of enemy planes increased until it was quite evident that they were not from a single carrier. When the Admiral and his staff realized this, their optimism vanished. The only way to survive was to launch the planes at once. The first enemy carrier planes to attack were 15 torpedo bombers. (Torpedo Squadron 8 from the USS Hornet). All 15 planes were shot down, and the sole survivor was Ens. G. H. Gay, who was rescued by a Navy Catalina the next day. A picture of Ens. Gay is on display in the Midway diorama).

The distant wings flashed in the sun. Occasionally one of the specks burst into a spark of flame and trailed black smoke as it fell into the water. Our fighters were on the job, and the enemy again seemed to be without fighter protection. Presently a report came from a Zero group leader: "All 15 enemy torpedo bombers had been shot down." Nearly 50 Zeros had gone down to intercept the unprotected enemy formation.

Again at 0930 a lookout atop the bridge yelled: Enemy torpedo bombers , 30 degrees to starboard, coming in low!" This was followed by another cry from a port lookout forward: "Enemy torpedo planes approaching 40 degrees to port!" The attackers closed in from both sides, barely skimming over the water. Flying in single columns, they were within five miles and seemed to be aiming straight for the Akagi.. Of the 14 enemy planes which came in from starboard , half were shot down, and only 5 remained of the original 12 planes to post. The survivors kept charging in as Akagi opened fire with antiaircraft machine guns. At last the moment the planes appeared to forsake the Akagi, zoomed overhead and made for Hiryu to port and astern of us. Through all this deadly gunfire the Zeros kept after the Americans, continually reducing their numbe

Seven enemy finally succeeded in launching their torpedoes at the Hiyru, five from her starboard side and two from port. A total of more than 40 enemy torpedo planes had been thrown against us in these attacks, but only seven had survived long enough to release their missiles, and not a single hit had scored. Nearly all of the raiding enemy planes were brought down.

FIVE FAITHFUL MINUTES:

At 1020 Admiral Nagumo, gave the order to launch when ready. On Akagi's flight deck all planes were in position with engines warming up. The big ship began turning into the wind. Within five minutes all of her planes would be launched. Five minutes! Who would have dreamed that the tide of battle would shift completely in that brief interval of time.

At 1024 the order to start launching came from the bridge voice tube. The Air Officer flapped a white flag and the first Zero fighter gathered speed and whizzed of the flight deck. At that instant a lookout screamed "Hell-divers". The plump silhouettes of the American dive bombers quickly grew larger, and then a number of black objects floated eerily from their wings. Bombs! Down they came. The terrifying scream of the dive bombers reached the decks first, followed by the crashing explosion of a direct hit. There was a blinding flash then a second explosion.

The attackers had gotten in unimpeded because our fighters, which had engaged the preceding wave of torpedo planes only a few moments earlier, had not yet had time to regain altitude. Consequently, it may be said that the American dive bombers' success was made possible by the earlier martyrdom of their torpedo planes. Also, our carriers had no time to evade because clouds hid the enemy's approach until he dove down to the attack. We had been caught flatfooted in our most vulnerable condition possible - decks loaded with planes armed and fueled for attack.

Bomb-Hits on Akagi

Bomb-Hits on Kaga

The Kaga and Soryu had also been hit and were giving off heavy columns of black smoke. Akagi, had taken two direct hits, one on the after rim of the amid ship elevator, the other on the rear guard on the portside of the flight deck. Normally, neither would been fatal to the giant carrier but induced explosions of fuel and munitions devastated whole sections of the ship, shaking the bridge and filling the air with deadly splinters. As fire spread among the planes lined up wing to wing on the after flight deck, their torpedoes began to explode, making it impossible to bring the fires under control. The entire hanger area was a blazing inferno, and the flames moved swiftly toward the bridge. At 0350 on 5 June, the fateful order to scuttle the great carrier Akagi .

ALL but 263 members of the carrier's crew survived. Kaga which had been hit almost simultaneously with the Akagi in the sudden dive-bombing attack, did last as long as the flagship. Nine enemy planes had swooped down on her at 1024, each dropped a single bomb. The first were near misses. But no fewer that four of the next six bombs scored direct hits on the forward, middle, and after section of the flight deck. Furious fires broke out, seemingly everywhere.

Bomb-Hits on Soryu

Soryu, the third victim of the enemy dive-bombing attack received one hit fewer than the Kaga, but the devastation was just as great. When the attack broke, deck parties were busily preparing the carrier planes for take-off and their first awareness of the onslaught came when great flashes of fire were seen sprouting from the Kaga, some distance off to port, followed by explosions and tremendous columns of black smoke . Eyes instinctively looked skyward just in time to see a spear of 13 American planes plummeting down on Soryu. It was 1025.

The Hiryu was the only carrier left undamaged after the devastating attack. With no time to lose, The Hiryu immediately to launch an attack on the American carriers. The attack force consisting of 18 dive-bombers and 6 escorting Zero fighters , took off at 1040. The planes flew toward the enemy at an altitude of 4,0000 meters. On the way Two of his covering fighters, however., indiscreetly pounced on the enemy torpedo bombers, reducing Kobayshi's escort to only four Zero's. When still some distance from their target, the planes were intercepted by enemy fighters who took a heavy toll. Nevertheless, eight planes got through to make the attack. Two of these planes were splashed by American cruiser and destroyer gunfire, but six bore in on the enemy carrier, scoring hits which started fires and raised billowing clouds of smoke.

Three Zeros and 13 dive bombers, were lost in the attack. An enemy carrier had been hit and was sending up great columns of smoke, Admiral Yamaguchi concluded that it must have been hit by at least several 250 kilogram (500 lbs) bombs and severely damaged. What he did not know was damage control parties in the US carrier Yorktown had worked so effectively that by 1400 the carrier was again able to make 18 Knots under her own power.

The American force had more than the single carrier previously reported (Enterprise, Hornet and Yorktown) . Hiryu, now alone, faced three crack enemy carriers, only one of which had thus suffered any damage. And one of these carriers was Yorktown, which we thought had been sunk, or at least heavily damaged, in the Coral Sea Battle. Admiral Yamaguchi decided to launch another attack with all remaining planes, The force comprised of 10 torpedo planes (one from the Akagi) and 6 fighters (two from Kaga) which were then available in Hiryu.

Preparations were completed at 1245, and the 16 planes rose from the flight deck to head for the enemy. At 1426 the attack group spotted an enemy carrier with several escorts some 10 miles ahead. The flight leader ordered an attack. Protective enemy fighters tried to intercept but were promptly engaged by escorting Zeros while torpedo planes bored in toward the carrier. Swooping from an altitude of 2,000 meters to within 1 hundred meters of the water, the planes headed straight for the American carrier. At 1445 a radio message reported two torpedo hits on this ship, which was identified half an hour later as being of the Yorktown class.

No further details of the attack were known until the surviving aircraft returned and were recovered by Huryu at 1630. Only five torpedo bombers and three fighters, half the number launched, got back to the carrier. The pilots claimed one hit on the carrier and reported severe damage to a San Francisco -class cruiser, but later, information indicated that the claimed hit on the cruiser had actually been a Japanese plane splashing into the water nearby.

Post war American accounts show that around 1442 Yorktown, actually received two torpedo hits, successfully evading two others aimed at her. The two hits added to the damage inflected by the earlier dive bomber attacks, were enough to doom the ship. But, none of her escorts sustained any damage from this air attack.

Bomb-Hits on Hiryu

Hiryu was now almost devoid of planes, all she had left was only six fighters, five dive bombers, and four torpedo planes. While her own planes were attacking the enemy, Hiryu had been the target of repeated and relentless enemy strikes. Since sunup no fewer than 79 planes had attacked, and the ship had successfully evaded some 26 torpedoes and 70 bombs.

At 1703, just as the first reconnaissance plane was ready to take off, a lookout shouted, "Enemy dive bombers directly overhead." They had come in from the southwest, so that the sun was behind them, and having no radar, we were unable to detect their approach . Thirteen planes singled out Hiryu as their target. The ships captain ordered hard right rudder, and the ship swung, lumbering to starboard. This timely action enabled Hiryu to evade the first three bombs, but more enemy planes came diving in and finally registered four direct hits which set off fires and explosions. Columns of black smoke rose skyward as the carrier began to lose speed.

All four bomb hits were near the bridge, and the concussions shattered every window. The Deck surface of the forward elevator was blasted upward so that it obstructed all forward view from the control area. As the last of our carriers was hit and damaged, the enemy planes began devoting their attention to the screening ships as well. Hiryu finally slowed down to a halt at 2123 hrs and began to list which increased to 15 degrees as she continued to take on water. Hiryu's last battle cost the lives of 416 crewmen, in addition to the two commanders who elected to perish with the ship.

General Summary:

A direct result of the battle was the change in Japanese carrier construction and doctrine. Future carrier designs now included better damage control equipment and stronger flight deck armor; the consideration for refueling operations on the flight deck was introduced, as well as a complete rethinking of search and reconnaissance operations. The changes were honest and theoretically viable, but after Midway Japan had lost the initiative, thus making the changes too little too late in terms of effectiveness.

The heavy losses in carriers and veteran aircrews at Midway permanently weakened the Imperial Japanese Navy. The heavy losses in veteran aircrew (110, just under 25% of the aircrew embarked on the four carriers) were not crippling to the Japanese naval air corps as a whole; the Japanese navy had 2,000 carrier-qualified aircrew at the start of the Pacific war. The loss of four large fleet carriers and over 40% of the carriers' highly trained aircraft mechanics and technicians, plus the essential flight-deck crews and armorers, and the loss of organizational knowledge embodied in such highly trained crews, were still heavy blows to the Japanese carrier fleet.